Difference between revisions of "Interpretive framing"

(illustrative graphic) |

(Framing paper (PDF)) |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

[[category:manipulative tools]] | [[category:manipulative tools]] | ||

</hide> | </hide> | ||

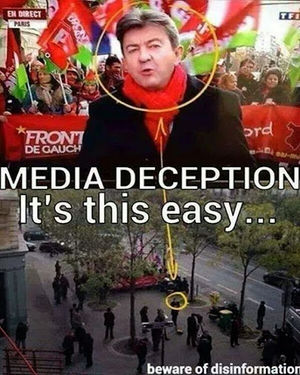

| − | [[File:14+-+1.jpg|thumb|A graphical analogy to interpretive framing: the camera crops out the empty streets beyond the staged crowd, implying that | + | [[File:14+-+1.jpg|thumb|A graphical analogy to interpretive framing: the camera crops out the empty streets beyond the staged crowd, implying that it is a representative sample of a much larger crowd all in agreement with the speaker -- when in fact most of the public has stayed home.]] |

==About== | ==About== | ||

[[Interpretive framing]], also known as '''political framing''' or just '''framing''', is a rhetorical device in which a complex [[issue]] is explained in simpler terms chosen to emphasize certain aspects of the issue and downplay others. It is related to [[cherry-picking]] in that it selectively highlights facts so as to paint a different picture from the one that a more balanced overview would give. | [[Interpretive framing]], also known as '''political framing''' or just '''framing''', is a rhetorical device in which a complex [[issue]] is explained in simpler terms chosen to emphasize certain aspects of the issue and downplay others. It is related to [[cherry-picking]] in that it selectively highlights facts so as to paint a different picture from the one that a more balanced overview would give. | ||

| Line 27: | Line 27: | ||

* The effectiveness of [[interpretive framing]] is probably best explained by [[memetic theory]]. | * The effectiveness of [[interpretive framing]] is probably best explained by [[memetic theory]]. | ||

* A poorly-chosen interpretive frame can lead to a [[false dilemma]]. | * A poorly-chosen interpretive frame can lead to a [[false dilemma]]. | ||

| − | + | ==Documents== | |

| + | * [[:File:J-Communication-2007-1.pdf|Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models]] (Dietram A. Scheufele & David Tewksbury, ''Journal of Communication'' #57 (2007)): "Drawing on various techniques for real-time message testing and focus grouping, Frank Luntz had researched Republican campaign messages and distilled terms and phrases that resonated with specific interpretive schemas among audiences and therefore helped shift people’s attitudes. In other words, the effect of the messages was not a function of content differences but of differences in the modes of presentation." | ||

==Links== | ==Links== | ||

===Reference=== | ===Reference=== | ||

* {{wikipedia|Framing (social sciences)}} | * {{wikipedia|Framing (social sciences)}} | ||

Latest revision as of 17:42, 11 January 2015

About

Interpretive framing, also known as political framing or just framing, is a rhetorical device in which a complex issue is explained in simpler terms chosen to emphasize certain aspects of the issue and downplay others. It is related to cherry-picking in that it selectively highlights facts so as to paint a different picture from the one that a more balanced overview would give.

It is typically used as a form of rhetorical deception, though it can be used non-deceptively (see Legitimate Uses).

Shifting the Window

One common deceptive usage of interpretive framing is to explain an issue in terms of two "opposites" that actually represent a fairly narrow range of possibilities -- leaving the audience with the impression that any views outside of this range are extreme, including views that are actually moderate.

Alternatively, if such a stance would be too difficult to believe, the issue can be presented as a choice between a moderate option and an extreme option (which the presenter does not actually believe in), leading many to conclude -- via the fallacy of moderation -- that a "compromise" lies somewhere in the middle, which is the position actually supported by the presenter.

This usage is often employed towards engineering a shift in the "Overton window" [W][1], which refers to the range of views considered acceptable for a politician to hold on a given subject.

Examples

Real: Obamacare

A fairly simple usage can be seen in CNN's interpretation of their own poll results (see page 2): 39% of respondents favored an action (Obamacare) and 13% thought it didn't go far enough, giving a total of 52% who presumably favored the action over no action at all.

Since the debate at the time was "should we take this action at all?" rather than "is this action sufficient?", clearly those 13% should have been counted as being in favor. CNN, however, added these numbers to the 43% who opposed any reform and reported that "59 percent of those surveyed opposed the bill". By framing the debate as being about "support for Obamacare" rather than "support for reform", they were able to give the impression that 59% were against reform without actually saying anything untrue.

Fictional: Liberals

A more hyperbolic example which, although fictional, is entirely consistent with views expressed by right-wing pundits such as Ann Coulter: "Are liberals evil, baby-eating monsters, or just disloyal and anti-American? We look at both sides of the issue."

Legitimate Uses

The only justifiable use of this technique seems to be when an issue has already been framed in terms that are unfair; an alternate framing may make it easier to see this unfairness, especially for those not inclined to look past the surface. However, this is generally playing to the strengths of those who would distort the truth rather than seek it, and does not really resolve anything.

Related Pages

- The effectiveness of interpretive framing is probably best explained by memetic theory.

- A poorly-chosen interpretive frame can lead to a false dilemma.

Documents

- Framing, Agenda Setting, and Priming: The Evolution of Three Media Effects Models (Dietram A. Scheufele & David Tewksbury, Journal of Communication #57 (2007)): "Drawing on various techniques for real-time message testing and focus grouping, Frank Luntz had researched Republican campaign messages and distilled terms and phrases that resonated with specific interpretive schemas among audiences and therefore helped shift people’s attitudes. In other words, the effect of the messages was not a function of content differences but of differences in the modes of presentation."